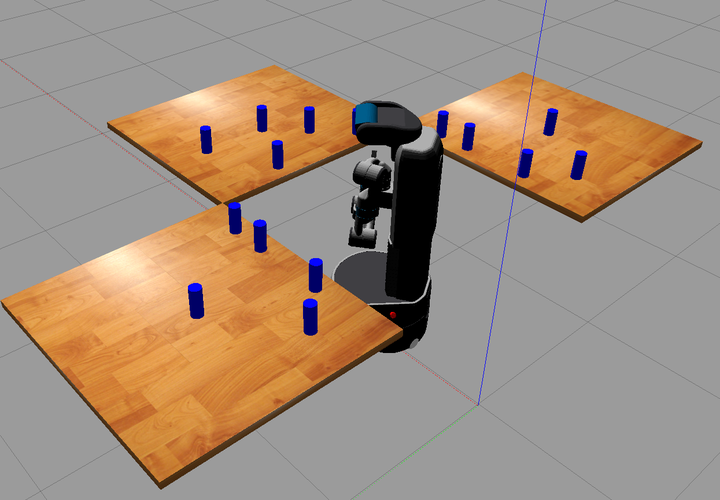

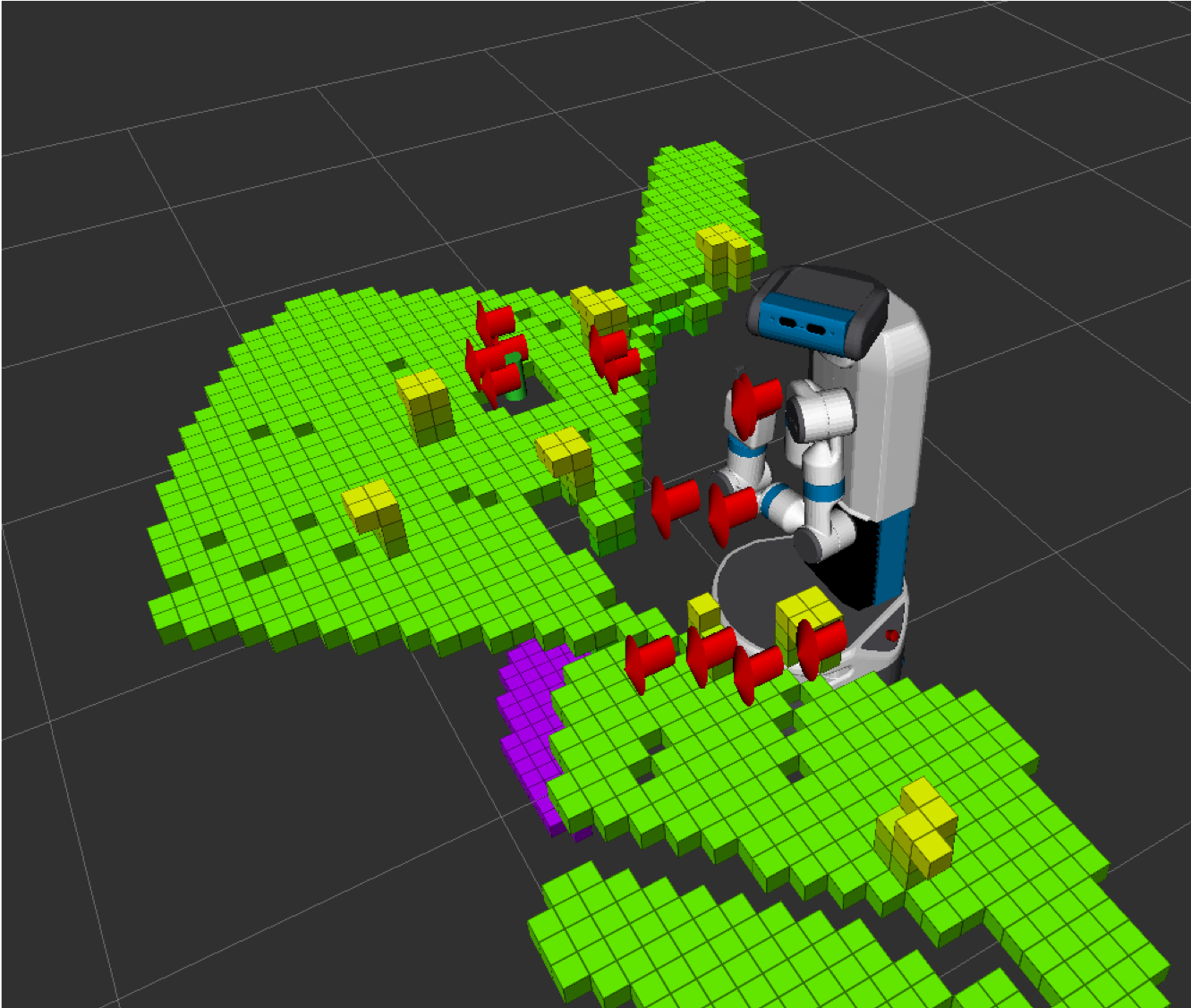

Fetch robot in the test environment

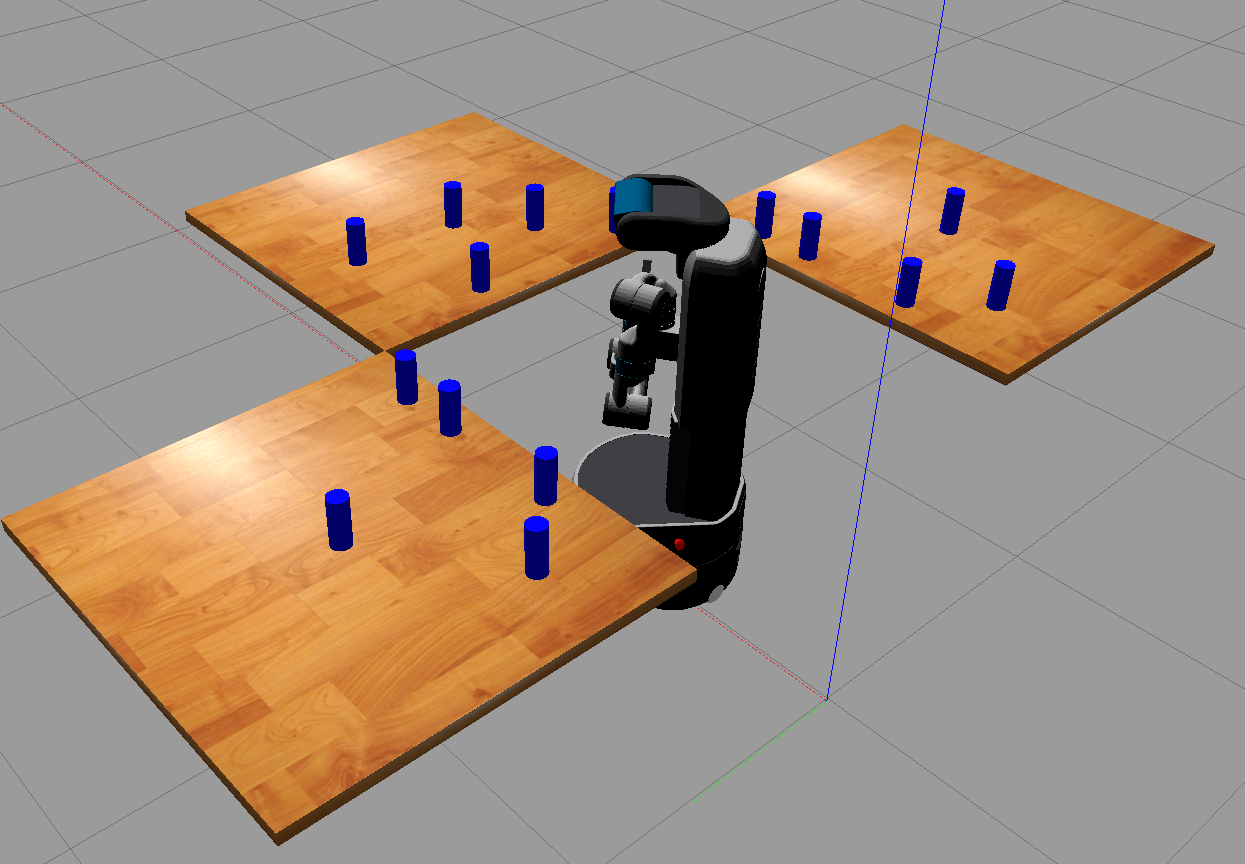

Fetch robot in the test environment

The objective of the project is to simulate the Fetch robot in a realistic environment considering uncertainty. In order to accomplish this we needed to take into account the complexity of a real robotic platform, starting with the topics covered during the course, i.e., kinematics, dynamics, control, but also others that were either briefly discussed or not at all, such as sensing, localization, motion planning, etc. Instead of building or analyzing all of these from scratch for the Fetch robot, we used a large software stack based on ROS (Robot Operating System). In the project, all of these were integrated in order to solve the problem of successfully planning and executing a grasping task in the presence of uncertain obstacles. The following are the main software components of the solution and a brief description of what was done in this project with each one:

-

Gazebo: It is the physics simulator where the world and robot are modeled. For the project I created the testing scenes by creating first objects (cylinders in this case) that represent cans and wooden tables. Each graspable object required a grasping pose that the robot knows beforehand that is used to compute the goal configuration for every can. The poses in ROS are represented as a $3D$ vector that represents the position and a $4D$ vector that represents its orientation as a quaternion. The figure below shows an example of one Gazebo scene

-

tf2: It is a ROS package that provided all the transformations between the different frames in the world. The robot geometry is already known for the the package and the transformations are given as abstract objects that can be operated as we operate transformation matrices. We used these transformations to compute the frame origins of the robot’s links that were part of the planned trajectory

-

MoveIt: It is a ROS package that provides access to a set of sampling-based planners available in OMPL. Plans are represented as a sequence of robot states (joint configurations) that are created from the group of joints that is used to plan. For this project we created a group for the 7 arm joints and the torso and therefore, each state could be represented as an 8-dimensional vector. This package also provides controller functions for executing the planned trajectories. The trajectory was required to be time-parameterized before passing it to the controller. The controller also provides a way to receive feedback on whether the given trajectory was successfully executed or not. This was required for the experiments

-

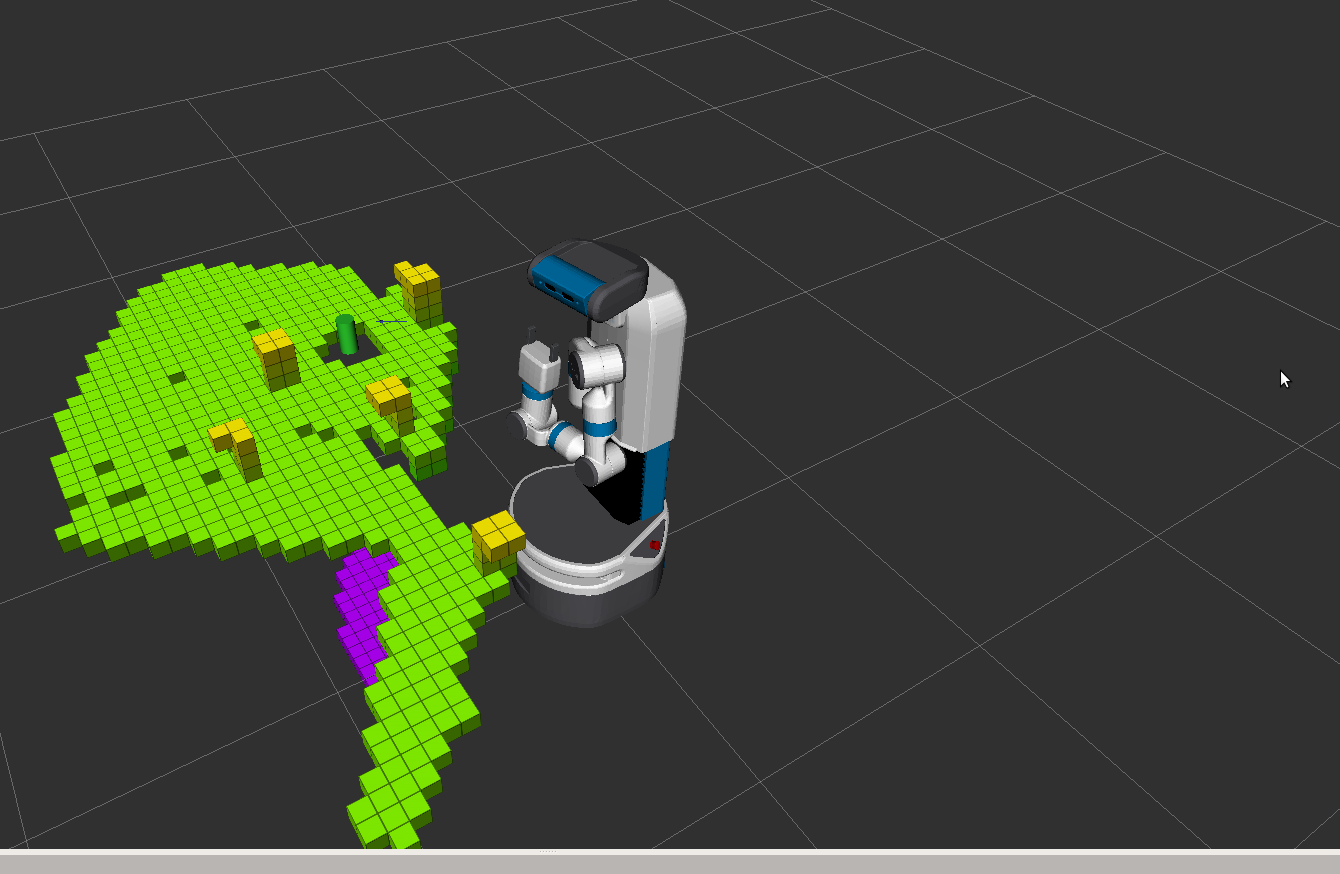

Octomap: It is a library that efficiently stores and manages data that comes from cloud points such as those captured with a RGB-D camera. The octomap represents the world by classifying parts of the space as free, mixed (free/occupied) or unknown. It creates boxes and each box is labeled as one of the possibilities. If the box is empty it stores it with a large resolution, if the box is mixed, it further split it into smaller boxes and it keeps doing that until all are free or occupied or a resolution limit is reached. It was used in this project to represent the scenes. In the experiments, we used a query function to know whether a given point in space was already explored or unknown. The figure below shows a scene representation using octomaps.

-

Quickhull: It is a library that provides fast computation of the convex hull of a set of points in three dimensions. It was required in the project to estimate the swept-out volume of a given trajectory

THE EXPERIMENTS

In order to succeed in the task of planning and executing a motion to grasp an object with sensor data, we needed to improve the scene representation. In many cases, it turned out that the robot was capable of successfully finding a plan but it failed in executing it because the scene was incomplete. This happens because the planner uses unknown space as free. The trivial solution of changing all the unknown space to occupied would not work because it becomes extremely likely that no path would be found since only a small part of the space is actually known by the robot. This assumption is also necessary to allow robots that do not know their entire environment to be able to explore it.

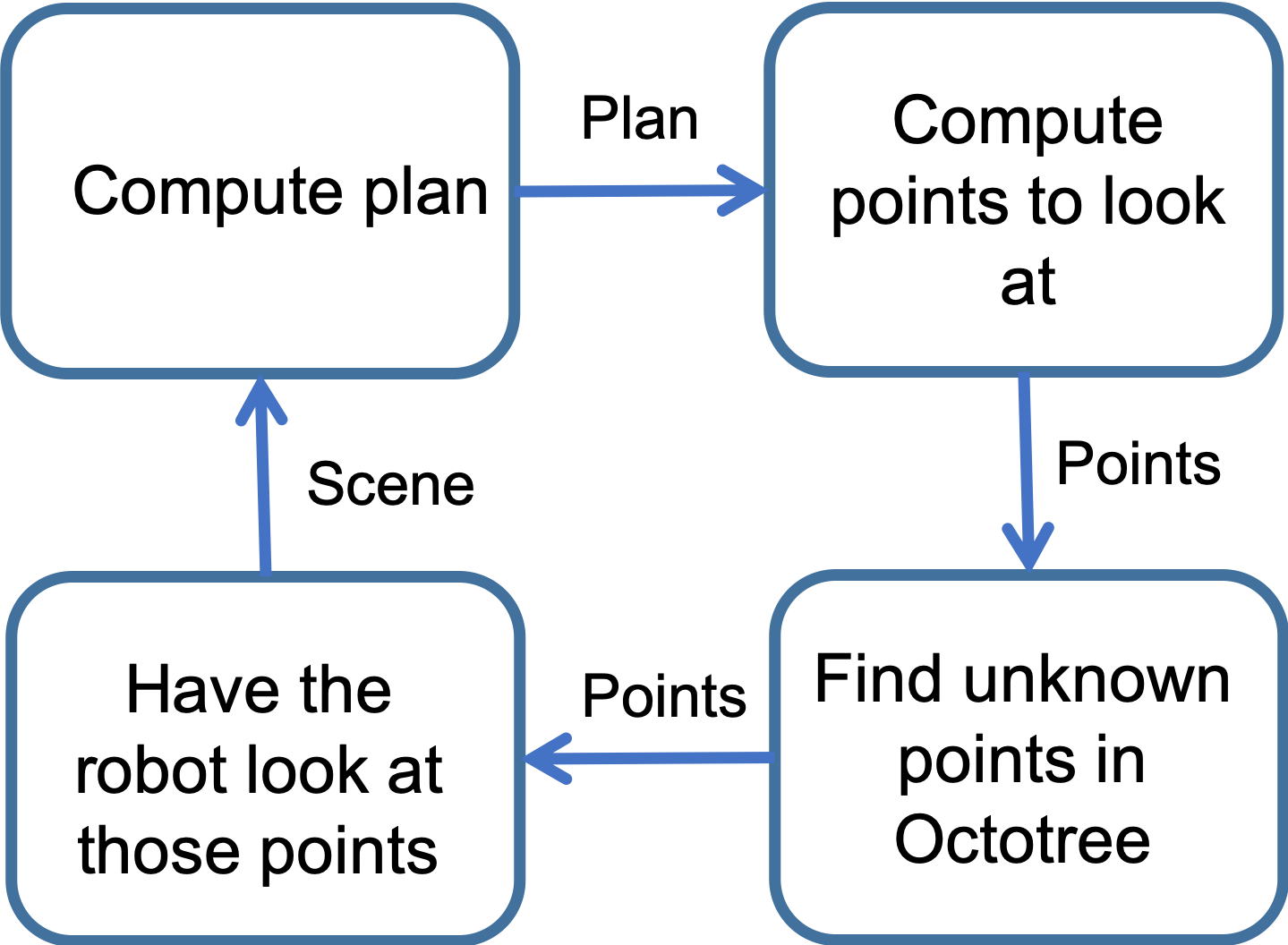

The figure below shows a diagram of the general proposed solution. The idea is to start a plan with the current known scene and then use this plan to extract points that the robot needs to explore before executing the trajectory to make sure that it will succeed (it won’t collide). After that, this points are examined to determine whether they are known or not and we command the robot to look at the set of those points that are unknown. Finally, the robot will create a new plan with the updated scene and will repeat this process until finding a safe plan (one where all the interesting points are in known space).

In order to decide which points are interesting to look at, we have explored four different strategies, described below:

- Object: Instead of using the planned trajectory, the robot only looks at the object

- Fixed points: The robot looks at two points at each side of the object

- Frame origins: The robot considers all the arm’s link origins for all joint configurations of the planned path

- Swept-out volume: The robot considers the volume swept-out by the arm if the trajectory were executed. The volume is estimated by computing the convex hull of consecutive joint configurations in the planned path

The figure below shows an image of the robot simulation looking at unknown points of the swept-out volume marked as red arrows. In order to compare the four strategies, we designed the following experiment: we place the robot base in a random position and orientation close to the tables. We randomly choose one can from all in the scene. Then, the robot implements the proposed methodology to create a plan to grasp the selected object using one of the strategies described above and finally the robot executes the trajectory. At that point, there are several possible outputs; the robot is able to succeed in the execution of the trajectory (i.e., it does not collide with obstacles and it reaches the grasping pose), the robot fails in executing the trajectory, the robot can not find a path to solve the problem at hand. For the cases of frame origins and swept-out volume strategies, the robot only executes the trajectory when the planner outputs a plan and all the interesting points are in the known region of the space. If the robot makes three planning attempts and it is still not able to find a completely safe path, it takes the risk and executes the current, potentially unsafe plan. This may or may not end up in collision but it is done to make sure that the algorithm won’t get stuck in infinite loops and also to avoid excessively large simulation times, especially because there might be points in space that could be occluded.

Each strategy was tested when 50 trajectories were executed and the time taken to complete the scene was measured for every strategy. Each motion planning problem is independent of the previous, meaning that the knowledge of the previous scene is not used before solving the next problem.

RESULTS

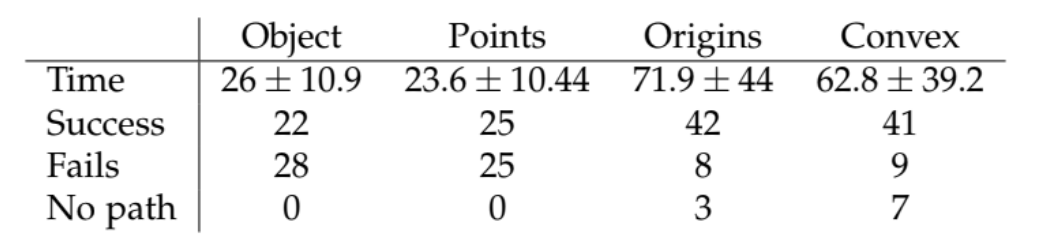

The table below show the results of the 50 runs for each strategy. As expected, the simple object and fixed points strategies take much less time in looking before executing the planned trajectory since they choose fixed points. However, it can also be seen that their probability of collision is much higher; much more than half of the different trials were not successfully solved. The frame origins and swept-out volume strategies effectively increase the probability of succeeding in the task execution since they take into account important points in the planned trajectory. Also, even though they take much more time than the simple strategies, this time is worth in applications where safety is a priority. Finally, these strategies can also create unsafe trajectories since a maximum number of attempts is considered. This number could be increased to further reduce the chances of obtaining unsafe trajectories at the expense of more time taken to look.

In the following video you can see the robot doing the described task for different sets of random scenes. The robot creates a trajectory and then looks at all the important points in the trajectory that are in unknown space (red arrows) until all of them are blue.