Neural Network Pruning - A review

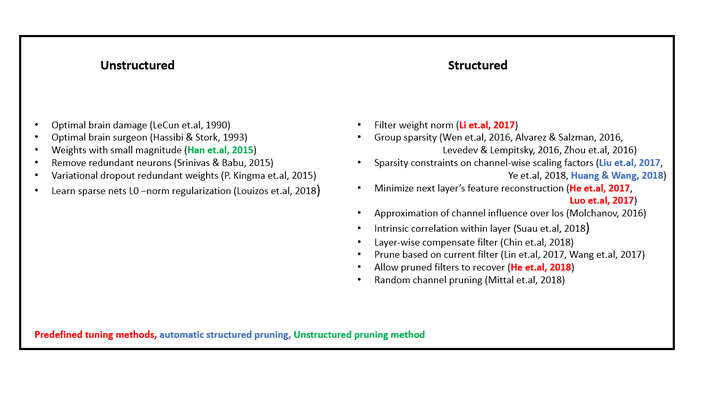

Pruning method’s summary

Pruning method’s summary

Machine learning - and especially deep learning - is a big trend these days; not only in research, but in many other domains. Large companies, start-ups, governments and many other actors have realized the importance on the use of massive available data to leverage their businesses and achieve more complex tasks than before. During the last decade, the size of machine learning models and the amount of data that they can efficiently process have significantly increased, in part due to the highly notable improvement of hardware technology especially tailored to meet the need of these models. Distributed computing has been an important resource to build large machine learning models. However, it is still not clear how to efficiently split the parameters of giant networks across distributed computing resources to achieve efficient training results. The nature of the gradient descent algorithm, that requires dense and sequential updates, leads to communication bottlenecks or accuracy degradation. Ideally, we would have asynchronous updates without hurting performance.

Other type of important applications for large machine learning models is in the mobile phones and low-resource devices. In these cases it is extremely important that training and inference costs (i.e., the costs of using the model to predict new values) are energy-efficient, since these may be implemented by the user in their own devices and long lasting battery life is a key requirement. Graphic Processing Units (GPU) are capable of achieving large amounts of computational operations, including matrix multiplication which is a key operation in training/inference processes of a Deep Neural Network (DNN). However, they are not, in general, energy-efficient. Only expecting that hardware designers reduce the energy cost of these operations at the hardware level is not possible since these enhancements may be slow, are mostly driven by commercial demands and may be highly expensive and risky.

An important common ground for the two scenarios described above is the fact that there are limits for hardware acceleration for machine learning models, either because algorithm characteristics restrict the massive parallelization on large distributed systems with high communication costs or because powerful available hardware are not very energy-efficient when building and evaluating machine learning models. One solution that will be discussed is to mostly rely on algorithmic improvements rather than only hardware acceleration.

Other important and related problem is the one of model representation. In general, we know that growing the size of deep learning models and the data used to build such models is beneficial to increase their accuracy. However, there are several issues that arise when trying to increase both. On one hand, the problem discussed above, about specialized distributed hardware, holds in this scenario since it is not possible to fit this amount of data and models into one single machine. Furthermore, all the required synchronism cost and larges amount of computation pose a big challenge. In these cases, conditional computing, where large parts of a network are active or inactive based on the current example, is a big promise.

One key concept that has allowed the realization of large models with state-of-the art performances under the constraints mentioned before is that of sparsity. One can think of sparseness in a deep network at different levels. For instance, one way to control the network complexity is dropout; a well known regularization technique that randomly turn off certain neurons of the network during training. Other coarser level of sparsification include the use of conditional computation where networks that are controlled by a gated network can be active or not depending on the specific input. This sparseness may bring ways to approach the desired asynchronous parameter updates since it makes the gradient also sparse. We will guide the discussion about sparsity for training deep networks in efficient manners by using the proposed papers. On one hand, the paper “Scalable and Sustainable Deep Learning via Randomized Hashing” is a type of adaptive dropout that uses randomized hashing to dramatically reduce the computation of neuron activations. The second paper “SLIDE : In Defense of Smart Algorithms over Hardware Acceleration for Large-scale Deep Learning Systems” presents the SLIDE framework which relies on algorithmic and data-structural design to minimize computational overheads. The authors provide a C++ implementation that can outperform the best implementation on tailored hardware by orders of magnitude. Finally, the paper “Outrageously Large Neural Networks: The Sparsely-gated Mixture of Experts Layer” written by Geoffrey Hinton and his group at Google shows a model based on conditional computation to increase a model capacity to be able to absorb huge amounts of data. Their models have up to $137$ billion parameters and can significantly improve state-of-the-art results at lower computational cost.

"Scalable and Sustainable Deep Learning via Randomized Hashing"

The core idea behind this paper attempts to solve the fundamental problem of achieving energy-efficient architectures for deep neural networks as well as asynchronous parameter updates in both training and inference. It does so by dramatically reducing the number of computations in the network by using sparsity. To achieve this, the authors propose to use a special form of adaptive dropout that relies on randomized hashing. In the idea of adaptive dropout, nodes in the network with low activation values are discarded. This has the described effect of controlling the network complexity but it also reduces the amount of computation since at every training/inference iteration, less operations are required. Previous approaches such as vanilla adaptive dropout and Winner-Take-all (WTA) require to choose the set of nodes for which the the activation is higher. To achieve this, these methods need to perform full computation of activations, although in the case of WTA only a certain percentage of activations are kept. An important idea behind these techniques is that of selecting neurons randomly according to some monotonic function of their activation, i.e., neurons are selected with higher probability if their activation is higher. The randomized hashing idea is that given an input $x$, its activation is a monotonic function of the inner product $w_i^{\top}x$ and therefore the problem of selecting a set of nodes with largest activations can be efficiently approximated to that of maximum inner product search using asymmetric locality sensitive hashing (LSH). In LSH the idea is to map similar items into the same bucket with high probability so that their collision probability is higher if they are close according to some similarity measure. All these results finally allow one to very efficiently find a set of neurons per training iteration with high activation by indexing the neurons into hash tables tailored for inner products. Since LSH achieves sub-linear performance in the search problem, there is a great benefit on using this technique instead of having to compute the activations for all neurons (as in vanilla dropout) or computing the active set in $O(n\log n)$ (as in WTA). At the end of the day, hashing is creating a probability distribution that is monotonic over the activations and applying the same core idea as in vanilla adaptive dropout but saving large amounts of computation.

This is a very interesting idea since it effectively shows that neurons into a deep neural network specializes and only contribute important information for some specific examples and furthermore it shows that a large amount of this redundant computation can be avoided by cleverly using efficient techniques such as LSH. In addition to this, the specific sparsity that arises by not considering the output of low activation neurons can be taken into account to perform sparse gradient updates. According to our discussion above, this is a highly desirable result since it easily allows one to perform distributed and asynchronous updates.

"SLIDE : In Defense of Smart Algorithms over Hardware Acceleration for Large-scale Deep Learning Systems"

In this paper the authors implement several implementation improvements over the sparse updates using LSH, such as initialization, the feedforward pass with hash table sampling, the sparse gradient update and others to finally attain a C++ implementation that is orders of magnitude faster than the best GPU implementation for state-of-the-art problems. Actually, the authors show a very good scalability of performance with respect to the number of cores mainly due to the asynchronous gradient updates. These papers express a very strong argument about the importance of clever algorithmic design with respect to hardware acceleration. Note that most of the ideas discussed here are not suitable for GPU implementation, since their performance drastically drops with sparse memory access. The successful of GPU computation is to achieve aligned-memory access to maximize bandwidth, which is generally, several times lower than processing power.

"Outrageously Large Neural Networks: The Sparsely-gated Mixture of Experts Layer"

This paper, written by Google, deals with the issue of model representation. The desired objective is to dramatically increase model capacity but not computation to be able to absorb vast quantities of data available today. Note that naively increasing model size (i.e., increasing the number of layers and neurons and therefore the number of parameters) easily results in an equal increase in the amount of computation and memory footprint that may not be possible to train using current state-of-the-art specialized distributed hardware. The authors propose the use of conditional computation and specifically the sparsely-gated mixture of experts layer. Under this model, a mix of expert networks is trained using specialized gating network that selects a sparse combination of the experts for each input example. The final model results in a model with a larger number of parameters when compared to traditional dense models but with sparse computations, since depending on the input example, the gating networks select a handful of experts only to evaluate, saving high amounts of computation. One could argue that the core idea behind this methods is that every input is sparse in the world of concepts and, similar to the ideas discussed before, one can use such sparseness to reduce the amount of computation required to achieve good performance. Also aligned with the previous discussion, the MoE model can easily be parallelized since each expert’s learning process can be designed to fit in one machine, greatly reducing the high cost of communication and synchronization. Also, note that this model is similar but different to that of ensembles. Possibly the most important difference is that all data need to be fed into inidividual learners in ensemble methods, while this is not true in the case of MoE. The gating network can compute its output first and based on this computation, only the output of the selected experts is required. Finally and very important is the necessity of balancing the expert utilization to avoid the phenomena that comes out when the same experts are chosen over and over again. At first, the experts are chosen almost randomly, since the gating network is not fully trained, but every time an expert is favored it is chosen more often producing experts with large weights. This balancing is achieved by introducing an additional term to the loss function of the model. The results of this proposal are clear. Using the type of sparsity introduced by the mixture of experts one can create models with amounts of parameters that were not possible before and use these models with even larger amounts of data to improve the performance of difficult learning problems.

The topic of sparsity on deep neural networks convincingly shows that inputs are usually sparse in the world of concepts and furthermore that this can be used to dramatically reduce the number of computations required for training/inference either for achieving energy-efficient implementations, as required in many commercial and industrial applications, or to significantly increase model capacity that allows us to solve larger and more difficult problems where huge amounts of data is available. The reason why this sparsity is possible and is a good idea in deep neural networks may shed light on better understanding how the learning process of complex concepts and models works to create more sophisticated learning algorithms.